You Are Not a Tree

"How long are you going to wait before you demand the best for yourself?" — Epictetus

In Ricky Gervais’s Netflix show After Life, he asks a 100-year-old woman about her life.

“You must’ve seen a lot, though? A hundred years.”

Her reply: “I was born in Tambury. I’ll die in Tambury. Very soon, I hope. I’ve seen fuck all! I may as well have been a tree.”

That image has stayed with me. A century of life in one place. Not because she couldn’t leave. Because leaving never occurred to her as a real option.

We talk about freedom of movement as though the only barriers are borders. Visa requirements. Passport colours. The geopolitics of where you happened to be born.

But most people who could leave don’t. They have the passport. They have the money. They have no war, no famine, no secret police. And still they stay. Rooted. As if an invisible fence runs through the mind.

I think about this because I left. Greece to the US, then the UK, and now Canada. Twenty years ago. And I’ve watched the people I grew up with stay put. Not because they can’t leave, but because leaving never occurred to them as a real option. The idea lives in the same mental category as “become an astronaut” or “win the lottery.” Technically possible. Practically absurd.

The first prison is fear of the unknown. We are all, to some degree, afraid of what we haven’t seen. A new country means new rules, new hierarchies, new ways of failing. You don’t know where to buy bread. You might not be able to speak the language, or speak it well. You don’t know if people are laughing with you or at you. You don’t know what you don’t know.

The familiar is a kind of anaesthetic. It numbs the part of us that would otherwise feel how small our world has become.

What changed for me was a trip I took at age 10.

I travelled from Athens to Montreal for a month during the early 90s. A boy named Nick lived down the street from my uncle’s house. He taught me to play baseball, and stayed patient with a kid who had never held a bat. His mother made us pizza and we ate it on his porch. We cycled around the neighbourhood with a bike I had to lean on the pavement just to reach the pedals.

Back in Greece, I didn’t know our neighbors next door.

The kids in Montreal played a game I’d never seen. There was no board. You made your own map, your own story. The game was Dungeons & Dragons.

My uncle gifted me the starter kit with the red dice set before I left. I tried to play it back in Greece with my brothers and friends, but nobody wanted to. No board, no pieces. They thought it was boring. I ended up playing alone, just to keep the memory alive.

Something restructured in my mind. I suddenly had another mental map of a place I had visited, that was oceans apart.

The world became smaller. Less frightening.

I learned that the map is not the territory. You can read about a place, hear stories, form opinions. But until you stand there, it remains abstract. And abstract things are easy to fear or dismiss.

The second prison is the cost of leaving. This one is real and heavy, and no amount of inspiration porn can make it lighter.

When I left Greece, I left my parents to age without me. I left my childhood friends behind. I left a version of myself that only existed in that context, the jokes that don’t translate, the references that fall flat, the person I was in a language I now speak only on the phone. You don’t just move to a new country. You become someone else. And the old self dies a little.

I haven’t been back in several years, and even then just a few days, passing through.

When I do go back, nothing is the size I remember. In my mind, my mother’s kitchen is expansive, the table where we ate, the kitchen window overlooking the street. In reality, it’s a small apartment. The hallway I ran through as a child takes four steps. The balcony fits two chairs. This isn’t criticism. It’s what distance does. The mind expands what it misses. Then you return, and the world shrinks back to its actual dimensions. You realize you’ve been homesick for a place that never quite existed.

My parents visit me now. It’s easier that way, I tell myself. And it’s true. It is easier. But easier isn’t the same as right.

There’s a depressing bit of math that floats around. Once you do the numbers, you realize you might only see your parents another ten or fifteen times before they die. It’s usually framed as an observation. It doesn’t feel like one.

I’ve already lost family members I never said goodbye to. Distance doesn’t prepare you for any of it.

I am the one who has to make the effort. My parents made the trip to Vancouver once. No one else has. I understand it, in a way. I’m the one who left. From their view, I created the distance. So I should be the one to close it.

I carry the weight of that distance. It doesn’t get lighter.

Growing up, I had two opposing influences on geography and choosing where to live.

Many of my relatives had immigrated to Canada and the US. They would visit us every summer in Greece, telling us how wonderful those places were. Wide roads. Big houses. Opportunities everywhere.

My family in Greece would dismiss all of it. “Anywhere you go around the world, it is all one and the same. I don’t see the point of moving anywhere else. Greece is the best place in the world.”

I was caught between these two stories until I visited Montreal at 10 and saw it for myself. The quality of life, the access to things that were unimaginable back home. When I returned to Greece and told my family what I had seen, they dismissed it. Just like they dismissed the relatives who had moved.

I was the only one from the family in Greece who ever visited. Everyone else had made up their minds without checking.

To my family in Greece, leaving was strange. Even reckless. Why would you go? What’s wrong with here?

For a long time, I didn’t know how to answer. I didn’t have the words for why their certainty felt incomplete. They weren’t wrong about Greece. They were working with the information they had. But they were evaluating a game they hadn’t played.

It’s like trying to explain 3D chess to someone who has only played on a flat board. They can’t fathom why you’d add another dimension. It looks unnecessarily complicated, maybe absurd. They judge your moves as mistakes because they’re evaluating them on a plane that doesn’t account for where you’re actually playing.

But you can’t see the next level until you’ve made the journey. The road unfolds only as you walk it.

I understand the appeal of staying. Leaving cost me something too.

My mother, years after reconciling with the fact that I had left Greece and was never coming back, shifted her perspective and advice. She started saying, “Don’t look back.” It reminded me of a line from the Italian film Cinema Paradiso, when the old projectionist tells the young Salvatore as he leaves his hometown: “Leave and never look back. Forget us.” It’s advice about growth. About letting go. My mother had become Alfredo.

Here is what no one tells you about leaving.

I knew that by going I might not see some people ever again. Then COVID happened. People died. I didn’t have the chance to consider that the last time I saw them would actually be the last. There was no goodbye that felt like a goodbye. I have to live with that and keep moving forward.

And yet, my family in Greece, the ones who live close to each other, they fight. They quarrel. They avoid each other for months. Proximity has not given them what I thought I was giving up.

I had seen the other side. And it looked like the street I grew up on. Familiar. Imperfect. Home.

The third prison is the one I didn’t understand until I’d already escaped it.

In school they made us read “Ithaki” by Kavafis. They made us memorize lines about hoping the voyage is long, about what Ithaka gives you and what it can’t. I was fifteen, and although I had visited Montreal at 10, I didn’t get it. The words were just words.

Nikos Kazantzakis, too. We studied him like a national monument, the great writer who left and kept leaving, who wrote from France, from Antibes, from anywhere but home. I memorized passages for exams. I didn’t understand why he couldn’t just stay.

Now I do.

In a 1955 interview on French Radio, Kazantzakis said something I’ve carried with me since I first understood it:

“The farther we are from our country, the more we think of it and the more we love it. When I am in Greece I see the small things, the intrigues, the foolishness, the inadequacies of the leaders, the misery of the people. But from a distance we do not see the fields so clearly and have more freedom to shape an image of the homeland worthy of total love. That’s why I work better and love Greece better when I’m abroad.”

I understood that in my body before I understood it in my mind.

There was something about the collective unconscious of the place I couldn’t sync with. The way things worked. The way they didn’t. The shortcuts everyone took because the straight path was for fools. I felt like I was swimming against a current that everyone else had accepted as the water itself. Staying meant shrinking into a shape that didn’t fit.

I love Greece. And I couldn’t breathe there.

This is another kind of prison. Not borders on a map. Not fear of the unknown. But the weight of a culture pressing against your lungs. Some people feel that weight and call it home. I felt it and called it a ceiling.

From Vancouver, I can see Greece clearly for the first time. The light. The sea. The way my father tells a story. The things worth loving, separated from the things that were killing me slowly.

Kazantzakis was right. Distance doesn’t diminish love. It purifies it.

The 100-year-old woman in Tambury had one map her whole life. She never tested it against the territory. My family in Greece told me everywhere was the same. They had never checked.

I don’t say this to judge them. I have my own boards I’ve never seen from above. My own dimensions I’m blind to.

But the ones I did explore taught me this: the world is not one and the same. And it is also not as foreign as we fear.

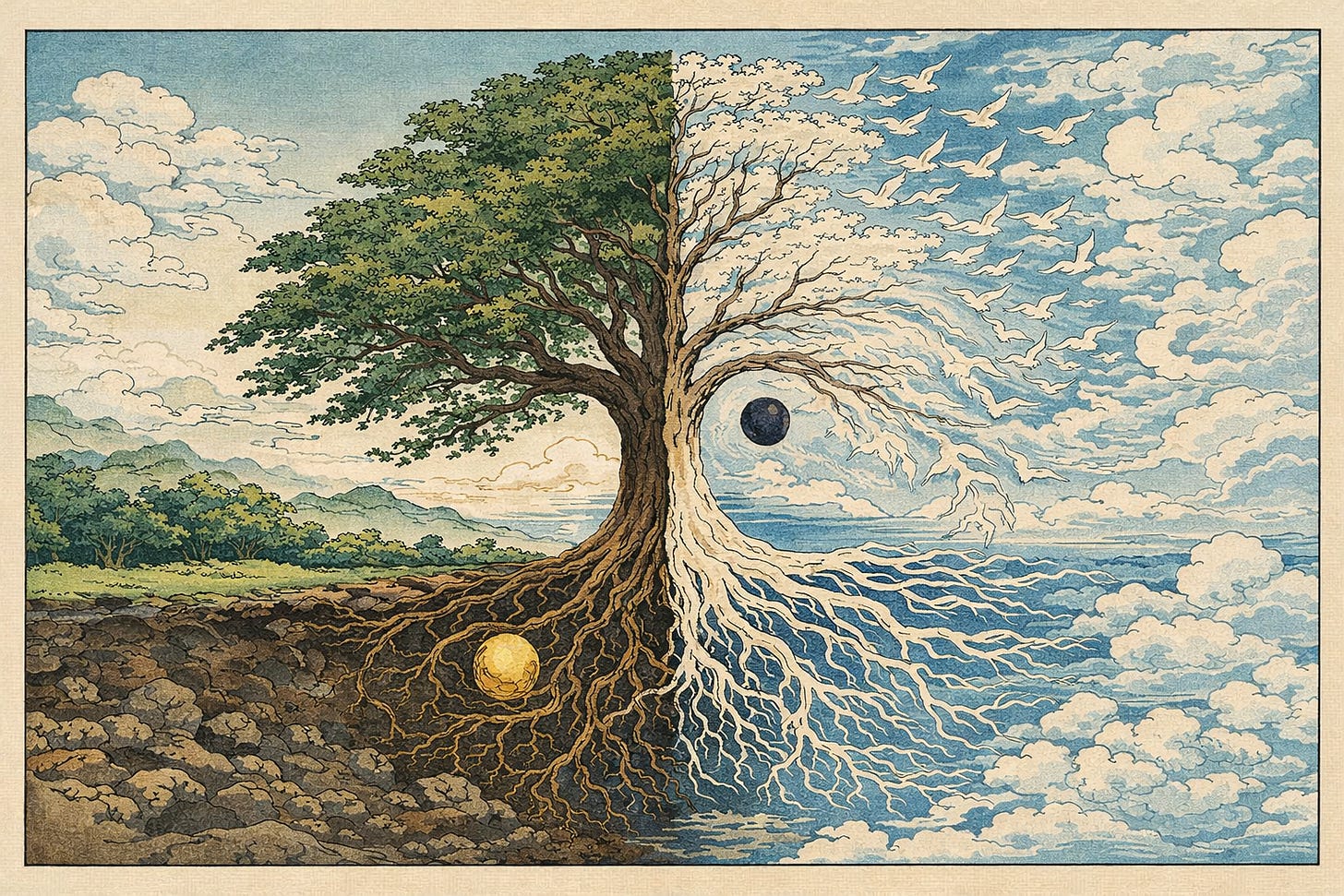

Trees can’t choose where they’re planted. But we’re not trees. We tell ourselves we are because it’s easier than admitting we have a choice. And that choosing is terrifying, and costly, and might be the only way to become who we’re supposed to be.

I am freer than my grandfather could have imagined. I am also more alone. Both are true. I carry the cost. And I would do it again.

The red dice are still in storage in Athens. Last year, I bought my son his own set. I told him the story.

You are not a tree.